A few years ago, an Alaskan climber named Sam Johnson contacted me for info on climbing in the Neacola Range of Lake Clark National Park. In 1995, my frequent partner in climb, Kennan Harvey, and I went in there to try the North Face of Mt.Neacola, the range’s namesake.

Photo taken by Sam Johnson of the Medusa Face of Mt. Neacola showing Harvey/Donahue line and high point.

Kennan had climbed the first ascent of the peak a couple of years earlier with none other than the Legend himself, Fred Becky – although Fred was sick in basecamp during the ascent so Kennan and two other younger climbers bagged the FA via an ice climb on the south face. Durning poor weather, Kennan skied around to the north side of the peak and discovered the enormous north wall. Sporting 4500 feet of steep and technical terrain, Kennan was blown away and it didn’t take much convincing for him to talk me into going back with him for a go on the unclimbed face. I was 23 years old at the time, and the peak was the thing young alpinist’s dreams are made of - remote, hard, unclimbed and unknown. Perfect.

The Neacola range is a phenomenon of compact, complex terrain, with steep, pointy summited peaks rising from small and convoluted glaciers. We flew out of Kenai with a pilot named Doug Brewer and were dropped on a glacier we named the Lobster Claw for its distinct shape on the map.

For the first time in many alpine adventures together, Kennan and I decided it would be a good idea to take a radio. As Doug flew away after dropping us off, Kennan tried the radio. Nothing. It didn’t work. Should have done the radio check while Doug was still on the glacier. Oh well, situation normal. No radio.

It stormed for all but one day of the next 25 days. We mostly skied our brains out, bagging peaks and skiing steep faces and tight couloirs on untouched peaks. When our pick up date was nearing, we decided to go climbing in the storm just to see how far we could get. The weather did improve a little, and after a couple of days of dragging a haul bag and portaledge up a complex alpine wall, we got sick of big wall style and decided to just go for a single push as far as we could from our portaledge camp 1500 feet up the wall.

For 24 hours we sorted through some of the most difficult and diverse climbing either of us had ever done or ever will do. Tricky aid, hard free climbing, steep ice and bizarre route-finding kept us focused like racecar drivers for hours on end.

One pitch in particular stands out in my mind as if it were yesterday instead of 20 years ago. I removed my crampons for tenuous aid climbing off the belay, and after 40 feet of A3 insecurity I placed a good piece of gear below a free-hanging dagger of ice. In those days, climbing free hanging daggers was not yet standard fare even at a crag area, let alone a half-mile off the deck, with another 1500 feet to the summit. I’ll never forget putting my crampons on from my last aid piece and chipping delicately up the dagger onto steep ice above. When the ice ran out, an overhanging corner of technical stemming took me to the end of the rope. I’d just used every climbing trick I knew in a single pitch of climbing.

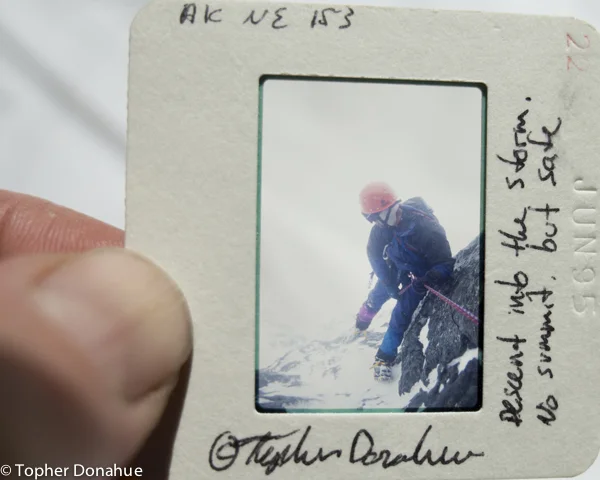

With the summit ridge less than a pitch away of easy terrain, the weather deteriorated into a spindrift nightmare, pummeling us for hours. Our bivy kit consisted of a down jacket and a bivy sack. Kennan took the jacket and I took the sack. We stood on boot-sized ledged chipped out of the ice all through the thankfully short Alaskan spring night.

When it was light enough to climb again, we made one of those decisions we’ll always wonder about – could we have made it? The weather was dismal, and Kennan’s hands were too cold to even rig his rappel device. Maybe we could have made it, but had we not made it, I wouldn’t be here today to share the story. We were really far out there – farther than I’ve ever been in my life. Nearly 3000 feet above our portaledge, in the middle of a mountain range nobody even knew about, with no way of contacting even the one guy, our pilot, who knew where we were.

We decided to go down, and rappelled into the whiteness. Upon reaching the portalege, we collapsed for a full day before we had the energy and hydration to continue down the wall below.

This year, Sam made it into the Neacola Range and took some photos of the face Kennan and I tried. In the process of online discussion with Sam and his friends, they asked if we had any climbing photos from the ascent. I was about to scan some of my slides, but decided for a more fitting way to share the experience and the world of adventure story-telling before Facebook, Instagram, GoPros, drones, and even the Internet, I would photograph the slides themselves.

I wonder how we'll tell stories in another 20 years...